Re-posted from NK News with corrections

By Mark P. Barry, April 15, 2012

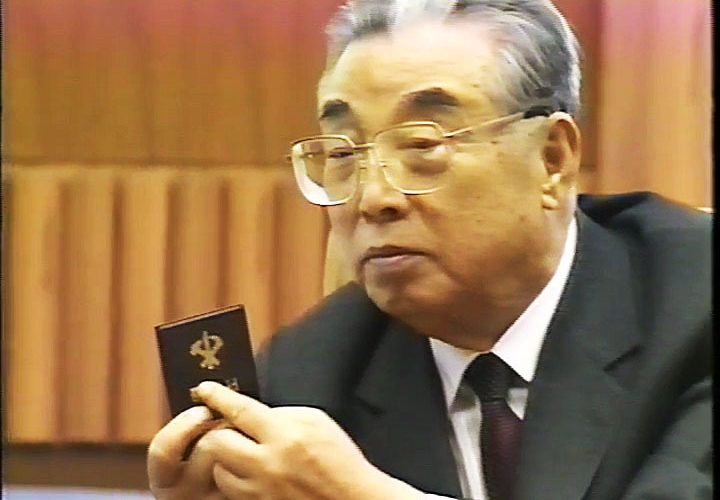

(Above) Kim Il Sung pointing to the meaning of the Korean Worker’s Party emblem (using Kim Yong Sun’s party card) at the meeting the author attended on April 16, 1994.

The first (non-communist) Americans to meet North Korea’s president Kim Il Sung [after 1948] likely were journalists Harrison Salisbury of The New York Times, and Selig Harrison, then of The Washington Post, in 1972. Congressman Stephen Solarz (D-NY) was the first U.S. public official to meet him in 1980, and Rev. Billy Graham later met him in 1992 and 1994. Little did I realize when I met Kim Il Sung on April 16, 1994, weeks before his death, I would be among a very small group of Americans ever to do so. On April 15 [2012], North Korea celebrates the 100th anniversary of the birth of the “Eternal President,” perhaps the North’s biggest celebration ever. Kim ruled North Korea for nearly half a century, far outliving Stalin and Mao, and holding power from Truman through Clinton. More importantly, Kim Il Sung embodied North Korea, a country and people he molded in his image. His legacy is now carried on by the young Kim Jong Un, who, North Koreans are constantly reminded, resembles his grandfather.

* * *

I was senior staff in a delegation organized by a Washington, DC-based NGO, the Summit Council for World Peace, an association of former heads of state and government, that arrived in Pyongyang at the time of Kim Il Sung’s 82nd birthday. The group was chaired by a former President of Costa Rica, Rodrigo Carazo, and included a former Governor General of Canada, former Egyptian prime minister, former chief of staff of the French armed forces, a U.S. think tank executive, and CNN’s chief global news executive, among others. TV crews also came from CNN and Japan’s NHK (journalists included Mike Chinoy, Josette Sheeran and Michael Breen). The Council had a prior record of successfully arranging meetings with Kim Il Sung, and Carazo himself had met Kim several times in the past.

Mid-morning on April 16, 1994 – the day after Kim’s birthday – our international delegation was brought in a fleet of black Mercedes to the Kumsusan Assembly Hall in Pyongyang, Kim Il Sung’s official residence. Our minders kept repeating how lucky we were for this opportunity. Inside, we lined up single file and were introduced individually to the waiting Kim Il Sung by a vice chairman of the Korea Asia Pacific Peace Committee. By Kim’s side was his superb English translator, and party secretary Kim Yong Sun, then the number three figure in North Korea (who later played an instrumental role in the 2000 inter-Korean summit) and chair of the Peace Committee. Kim Il Sung stood and walked on his own without assistance, but had a military aide nearby just in case. He did not seem to be wearing a hearing aid. His handshake was firm, he did not look overweight and appeared to be in good health, although his voice was rather gravelly (a Korean affairs analyst later told me this was because Kim used to smoke a lot). Very noticeable on the right side of his neck was a baseball-sized growth, which was benign, but because of its location, was said to be inoperable; official photos of Kim always were taken from a leftward angle to hide the growth.

After our official greetings, we were brought before a huge mural in the main lobby of the palace for our official photos. They were taken in two groups: the former heads of state and government and other senior members of the delegation, and the journalists. As with other visitors to the palace, we later each received a copy of the official photo with the date gold-stamped.

We were then escorted into the palace conference room with a long table that could accommodate two dozen. Each place setting had a pen, writing pad, and microphone, as well as coffee cup and dish of small candies. After we sat down, the window curtains and room lighting were remotely adjusted. Noticeably, neither the translator nor Kim Yong Sun sat too close to President Kim. On the DPRK side of the table were also Kim Yong Sun’s wife, and two other officials from the Asia Pacific Peace Committee.

President Carazo, who founded the United Nations Peace University in Costa Rica, spoke first, thanking Kim for receiving our group, and noting we were a goodwill delegation that had come to the DPRK for the sake of peace in the entire peninsula. President Kim responded that he regretted that we did not come through Panmunjom because we could then better understand the division of Korea (in fact, we had sought permission from the ROK to do so, but the Kim Young Sam administration denied our request; however, we later traveled to the northern end of Panmunjom, as well as a small town by the DMZ that clearly was not a Potemkin village). Kim added that months earlier, Congressman Gary Ackerman (D-NY) had come to see him, and had returned to South Korea by way of Panmunjom, becoming the first American to do so since the Korean War.

Kim then began to expound. He said, “We always open our doors widely. Our only secrets have to do with the military. But apart from that, we are ready to open to the outside.” The nuclear issue, which had become quite serious by that time, was not brought up in this meeting, but was left to the journalists. Later that day, Kim Il Sung would personally hand to Josette Sheeran, then managing editor of The Washington Times (later Executive Director, World Food Programme, and President of The Asia Society), a booklet of his written answers to her questions, that included his candid responses about the DPRK nuclear program. The full-length interview, her second with him, was published on April 19. I do not believe his answers were ghost-written, but were largely dictated by Kim, because the tone had the same unmistakable authority as when I heard him speak.

Kim then proceeded to boast that in North Korea “there are no beggars, no unemployed, no homeless.” He recalled asking Rev. Billy Graham if there were beggars, unemployed and homeless in America, to which Graham said “yes.” While this statement seems laughable in the context of the severe food shortages that North Korea would endure from 1996 on, it was not a ludicrous thing to hear about the North in 1994. Flying in on Air Koryo, President Carazo had peered out the cabin window and saw the expanse of freshly planted rice paddies, and said it appeared North Korea could produce enough food to feed itself. Kim Il Sung also told a story about a visiting Hong Kong businessman who had lost his wallet in a Pyongyang hotel with $10,000 in it; his wallet was returned to him within two hours, everything intact, Kim said.

Kim then turned to what seemed a favorite theme of his: what made the DPRK different from the Soviet Union, China and other communist states. He said, “After 1945, I tried to find intellectuals to rebuild the country, but could only locate a handful. The partisans who fought with me against the Japanese knew how to fight, but not how to build institutions.” The Japanese in their 35-year colonial rule, he said, left no college functioning in the North. “So I had to start my own, which became Kim Il Sung University, and then other schools. Today [1994], there are 1.76 million intellectuals out of a population of 20 million, almost one out of ten citizens.” What still impresses me about his point is how North Koreans value education, are inquisitive, and possess great human capital that can easily be trained to a high-level of professional skill.

Suddenly, Kim Il Sung leaned to the side and asked Secretary Kim Yong Sun for his Korean Workers Party membership card. I will never forget the look on Kim Yong Sun’s face. He almost turned white, because even though President Kim wanted the card just to make a point, Kim Yong Sun did not know if the request meant something more serious, such as losing his party post. But as he handed the card to his leader, Kim Il Sung held it up and pointed to the large gold-stamped party emblem, consisting of the usual hammer and sickle, but also a calligraphy brush in the middle. “In 1946, I created this emblem for our party. The brush symbolizes our highest commitment to intellectual pursuits in every discipline. Our emblem is unique among communist parties in the world. This is an example of juche, doing things our own way. We did everything in our own way.” President Kim then handed the party card back to its relieved owner.

At this juncture, Bill Taylor, Vice President of the Washington-based Center for Strategic and International Studies (CSIS), who was meeting the North Korean leader for the second time, told Kim that he had not changed a bit from two years ago, and looked to be in good health. Kim responded, “I always live with optimism.” Eason Jordan, president of CNN International, greeted Kim on behalf of Ted Turner, founder of CNN, and expressed hope for a face-to-face interview, which did not materialize. Taylor praised Kim’s decision to allow in CNN and NHK as a very important step. In fact, CNN’s Mike Chinoy conducted the first live broadcast from Pyongyang during this trip, using state television’s satellite uplink.

The meeting ended and we adjourned across the hall for lunch. We sat at a large round table with white tablecloth, although most journalists sat at a second table. The northern Korean cuisine was extraordinary, including my first time to taste blueberry wine. Conversation became a bit more free-flowing. Kim was asked about the role of his son and successor, Kim Jong Il. He responded, “I am so proud of him. As an elderly man, I cannot read easily, and every day my son dictates reports into a cassette recorder so I can listen to them later on. But he keeps me fully informed. He is truly a filial son.” The North Korean leader also noted he likes to hunt, especially wild boar.

One participant asked him if he would like to come to the United States. He responded, “I have yet to visit the United States, but I hope to do so in the future.” Someone suggested he even come to the opening session of the United Nations General Assembly in New York in September 1994. Kim smiled. Though he likely feared flying, the State Department could not have prevented him from coming to the UN with other world leaders in attendance because Kim was head of state of a member nation.

According to one Korean affairs specialist, in Kim’s 1994 discussions with Billy Graham, a large U.S. National Council of Churches delegation, and former President Jimmy Carter, he frequently returned to his youth and engaged in a discussion of religion with curiosity. In a sense, he began to mellow, as older Korean men can be quite susceptible to this; among older overseas Korean men, there is an urge to return to one’s hometown in Korea. This seemed to me to be true based on my observation of Kim Il Sung that day.

After the banquet, we said our individual farewells to Kim Il Sung. Several participants told him they wanted to return to the DPRK with others so they could see the country for themselves. One even invited Kim to come to the U.S. to enjoy sport fishing. Kim seemed genuinely appreciative of each gesture. As we walked out of the reception room, Kim was left standing with just Kim Yong Sun, his translator and military aide. He seemed to regret seeing us leave. We were outsiders, non-Koreans, from Europe, the U.S., Canada, Japan, Egypt, and elsewhere. He appeared to enjoy nothing better than to tell us his story, one few foreigners in the non-communist world had heard. For Kim Il Sung, it was a rare opportunity, to get courtesy and respect from foreign leaders and let them know his legacy. We did not realize Kim had only weeks to live.

Kim Il Sung would see two more outside visitors in June 1994, Selig Harrison and Jimmy Carter, as the nuclear issue reached a fever pitch and both the Clinton and Kim Young Sam administrations prepared for a possible outbreak of hostilities. Carter’s historic trip as the first former U.S. president to meet Kim Il Sung,* defused the nuclear crisis, averted war and led to the 1994 Agreed Framework, which froze the DPRK nuclear program until 2003. Kim also told Carter he agreed to hold the first-ever inter-Korean summit that summer with Kim Young Sam. It was not to be.

Kim Il Sung died suddenly of a heart attack on July 8, 1994. We later learned that Kim knew he was dying and felt an urgency to initiate major policy measures while still alive to effect a strategic change; Kim Jong Il would have been unable to implement major policy change after his father’s death. Kim senior’s meeting with Carter was that pivotal moment, and U.S.-DPRK relations eventually were elevated to where, in October 2000, the top North Korean general, Vice Marshall Jo Myong Rok, greeted Bill Clinton in the White House and Secretary of State Madeleine Albright met Kim Jong Il in Pyongyang weeks later. The same pattern appeared to unfold last fall: Kim Jong Il knew he would not live long, and in his final weeks, set into motion policy initiatives, including toward the U.S., to pave the way for Kim Jong Un’s succession.

* * *

Kim Il Sung’s official residence became his mausoleum, renamed the Kumsusan Memorial Palace. Kim Jong Il, who died in December (2011), joined his father there. In February 2012, Kim Jong Un rechristened the mausoleum the Kumsusan Palace of the Sun, named for his father, but foremost for his grandfather, Kim Il Sung.♦

* Excellent sources for this trip include Marion Creekmore, Jr., A Moment of Crisis: Jimmy Carter, the Power of a Peacemaker, and North Korea’s Nuclear Ambitions, 2006, and Douglas Brinkley, The Unfinished Presidency: Jimmy Carter’s Journey to the Nobel Peace Prize (cf. Chapter 20, “Mission to North Korea”), 1998. Bill Clinton was the only former U.S. president to meet Kim Jong Il, in 2009. President Donald Trump met Kim Jong Un three times in 2018 and 2019.